An important division of things in Crusius’ ontology we didn’t consider last time is that of incomplete things. An incomplete thing, Crusius explains, is such that, if it should exist, it must be connected to some other thing. A good example would be a location of a thing in relation to other things: clearly, if a location exists, there must be a thing which is located in this manner.

In addition to such external circumstances (umstände) like location, examples of incomplete things, Crusius says, are provided by the relation of subsistence. Crusius has inherited this notion from tradition, but as it is simple and cannot therefore be really defined, it is difficult to understand what is meant by something subsisting in something else. Crusius does provide illustrations of the relation, examples being relation of a certain shape to a piece of matter, understanding to a soul and even foot to a human being. Here, that which subsists Crusius calls property (rather confusingly, because properties were also parts of essence) or predicamental accident, while that where something subsists is called a subject.

In a rather inconsistent manner, Crusius sometimes speaks as if subjects were the stable element in the relation, although in many other places he underlines that subject and its accidents are incomplete and only their combination - essence or substance - is the true complete thing, just like matter and shape or form are just two aspects of a shaped material object, like a book.

Subsistence relation forms chains, with subjects subsisting in further subjects, Crusius explains, just like science subsists in understanding and understanding in soul. Crusius suggests that these chains cannot go on indefinitely, but there must be some absolute subjects, which do not subsist in anything else. Well, to make the matters more difficult, Crusius suggests then that even absolute subjects can subsist in a further subject, just not like a property subsists in a subject.

In some cases a subject is necessarily connected to a certain property, in other cases not, Crusius says. Examples of the latter would be, on the one hand, red colour of a house, on the other hand, person’s ability to speak Latin. These two examples are very different in nature. Someone might not have an ability to speak Latin, without having an ability to speak anything else, Crusius notes. Then again, if the house is not red, it still has some colour. Colour is what Crusius calls a house’s possible way of existence or its determination.

A thing with some determinations missing cannot really exist, Crusius explains, although we can think of such an indeterminate thing as a subject of further determinations. Just like Wolffians, Crusius defines an individual thing as being fully determinate. With all its determinations, an individual is differentiated from all other individuals, while abstractions from individuals can exist only in several individuals.

Crusius also divides properties into positive and negative properties. This division is linked with the notion of determinations in the sense that when we think of a negative property, we then implicitly think of some positive property, but only indeterminately (what is not yellow is still coloured somehow). Crusius divides negative properties further into merely negative and privative determinations (think how it is different to say that coal is not alive and that JFK is not alive). Similarly, he divides positive properties into absolute properties and relations.

To further explain what makes property positive, Crusius states that all of them are forces, that is, they make other things possible or even actual by themselves or with the help of something else. This leads Crusius to deal with the notion of causality. Epistemically, he says, causality is justified by it being impossible to think of something being generated without being an effect of some cause. The corresponding principle of sufficient reason, Crusius insists, cannot be deduced from the principle of non-contradiction, because there is no contradiction when things are different at different times. Furthermore, he continues, causality is a concept we cannot really define - it is so simple that we can only show how this concept can be abstracted from our experience by noting e.g. how our experiences of fire and warmth are linked to one another, without one being part or determination of the other.

Crusius also links causality to what he calls a principle of contingency: what can be thought as not existing must have really not existed at some point in time. The idea behind this principle is that if we then find such a contingent thing existing at some point, it must have been actualised by some force.

Forces or causes are for Crusius one type of ground. There are also other types of ground, he continues. For instance, because a triangle has sides of certain lengths, it must also have angles of certain sizes. Here, the lengths of the sides are a ground for the sizes of the angles, although the sizes clearly do not cause the angles to be of a certain size. Crusius calls such an existential ground.

Both causal ground and existential ground fall under what Crusius calls a real ground: the idea is that in these cases what is grounded is something outside thought. Ideal ground, on the other hand, Crusius defines as something generating knowledge and conviction of something. He also divides ideal grounds into a posteriori and a priori grounds. In an a posteriori ground the concept of what we are about to prove is already present, while the ground at most reveals that this something exists. A priori ground, on the other hand, generates also an idea of what we are grounding.

Returning back from this detour to an essence and its properties, we find Crusius dealing with what he calls the fundamental essence of a thing and attributes, which are constant properties, grounded in the very fundamental essence of the thing. Some of these attributes are necessary or essential: the existence of these attributes is inevitable, once the fundamental essence behind them is supposed to exist. The other type of attribute Crusius deals with is natural attribute or property, which is present in things of certain type usually, but could be absent in extraordinary cases, although the fundamental essence of the thing would remain the same. He notes also that some attributes are based only on the fundamental essence of the thing, while others are based also on external, but constant causes.

Crucius notes also that some attributes mark a real existence of some condition, while others mark only a capacity for something, activated by external causes, contingent activity of the fundamental essence or both. Such activation of capacities makes then possible the change of contingent properties or modi of a thing. By a modus Crusius refers to properties that make an indeterminate thing more determinate by adding to constant properties something variable, which could be replaced by another modus.

Crusius also considers the distinction between a necessary and a contingent fundamental essence. In a necessary fundamental essence properties constituting the fundamental essence of a thing cannot be separated from one another without supposing some contradiction. In this case, also the attributes flowing from the fundamental essence of the thing must be necessary, and indeed, the only thing that can be up to chance is whether the thing itself exists at all. Contingent fundamental essence, on the other hand, refers to a fundamental essence, where some of the constituent properties can be removed without any contradiction. Crusius notes that all finite substances have in this sense a contingent fundamental essence.

These notions lead Crusius to consider a more general question: what does it mean when we consider whether presupposition of a certain determinate essence contradicts a presence or absence of a certain property? His answer is that all this question can reveal is that presence or absence of a property is necessary for a certain concept. Thus, we cannot add a fourth angle to a triangle, without making it not agree with the concept of a triangle. This does not mean that the properties of the thing would be necessary outside our concepts (e.g. a triangle could be changed into a quadrangle). Such a substantial necessity of properties is present only in the cases, Crusius explains, where removal of this necessary property would make the thing incapable of even existing.

Näytetään tekstit, joissa on tunniste substances. Näytä kaikki tekstit

Näytetään tekstit, joissa on tunniste substances. Näytä kaikki tekstit

perjantai 13. toukokuuta 2022

keskiviikko 7. helmikuuta 2018

Joachim Darjes: Elements of metaphysics 1 - Connecting substances

While in previous post I discussed Darjesian notions of entity and substance, when regarded in abstraction from other entities and substances, now we shall see what happens when entities and substances are connected to one another. Darjes notes that these connections fall into three general classes, depending on whether the connection exists between mere entities, between both mere entities and substances or between substances. In case of the first kind of connection the things connected are regarded as just being impenetrable to one another. Example of a such a connection would be placing many entities into a same space so as to form a figure.

If in addition to or in place of mere entities substances are added to the connection, Darjes notes, we get forces to the equation. Such connections involve either the existence of substances or then their states – for instance, existence of certain substances might be connected with a state of one substance. In other words, such substantial connections concern various interactions between substances, for example, when one substance acts upon a passive substance or when one substance removes obstacles stopping some substance from acting.

All connections involving mere entities are extrinsic in the sense that it doesn't affect entities if we e.g. arrange them to form a figure. Thus, these connections are completely contingent. One might think that the case might be different with substantial connections, but Darjes notes that this is not so – substances can exist independently of one another, so there is no necessity that e.g. a substance affects another substance. Because no connections between entities or substances is necessary, Darjes says, these connections must ultimately be dependent on some necessary entity.

A particular type of connection Darjes mentions is the relationship between cause and what is caused. Like always, Darjes makes interesting divisions rarely seen in previous Wolffian philosophy. Thus,he notes when discussing cause or caused, one can firstly regard cause and caused as mere subjects – that is, as a material cause and caused – secondly as containing a reason for the possibility of something or having a reason of possibility in some other entity – this is what Darjes calls active/passive causating reason – and finally, as containing or having in something else a reason for actuality – active or passive causality. Like many other Wolffians before him, Darjes goes into great lengths in describing various causal notions, such as principal cause and instrumental cause or mediate and immediate cause, and we need not follow him in such a detail.

Just like almost all Wolffians thus far, Darjes defines the notion of space through the spatial relations an entity could have. Indeed, spatial relations are based on certain connections between entities, in which one entity cannot take the place of the other entities. Such space is then no true entity, but merely an abstraction out of real entities and their relationships. While spatial relationships are completely external to the entities or substances, if one adds activities to the equation, the connection becomes at least more internal. Darjes speaks of presence, by which he means the factor of one substance affecting another – the more a substance affects another, the more present it is to that other substance. Darjesian presence is then a much stronger relationship than mere spatial closeness – if one unites entities by bringing them close to one another, the union is merely external, while a union involving substances being present to one another is internal.

Before moving to more particular parts of metaphysics, Darjes finally considers the notions of infinity and finity, which he defines simply through the notion of perfection – finite entity is such that something can be more perfect than it, while an infinite entity is as perfect as is possible. The finity of an entity does not mean it couldn't be also perfect in some measure. It just isn't completely perfect and all perfection it has must belong also to the infinite entity. It is then immediately clear that all passivity, incompleteness and possibility of non-existence are signs of finity.

Already at this place in metaphysics, Darjes introduces Wolffian aposteriori and apriori proofs of God's existence, although he is, of course, not yet speaking of God. He notes, firstly, that since all finite entities are contingent, they must ultimately depend on a necessary infinite entity. Hence, if finite entities exist, an infinite entity surely must exist also (aposteriori proof). Since it is clearly possible that a finite entity would exist, an infinite entity must also be a possibility. Because infinite entity can be only impossible or necessary, it must then exist necessarily (apriori proof). We see here a similar dual role played by the two proofs as in Wolff's theology, the difference being that Darjes has to assume only the possibility of something finite.

Infinite and finite form then the major division of entities. Infinite entity is essentially unique, so no further division of that species is possible. Finite entities, on the other hand, can divide into further subspecies, depending on whether they are simple or complex.

If in addition to or in place of mere entities substances are added to the connection, Darjes notes, we get forces to the equation. Such connections involve either the existence of substances or then their states – for instance, existence of certain substances might be connected with a state of one substance. In other words, such substantial connections concern various interactions between substances, for example, when one substance acts upon a passive substance or when one substance removes obstacles stopping some substance from acting.

All connections involving mere entities are extrinsic in the sense that it doesn't affect entities if we e.g. arrange them to form a figure. Thus, these connections are completely contingent. One might think that the case might be different with substantial connections, but Darjes notes that this is not so – substances can exist independently of one another, so there is no necessity that e.g. a substance affects another substance. Because no connections between entities or substances is necessary, Darjes says, these connections must ultimately be dependent on some necessary entity.

A particular type of connection Darjes mentions is the relationship between cause and what is caused. Like always, Darjes makes interesting divisions rarely seen in previous Wolffian philosophy. Thus,he notes when discussing cause or caused, one can firstly regard cause and caused as mere subjects – that is, as a material cause and caused – secondly as containing a reason for the possibility of something or having a reason of possibility in some other entity – this is what Darjes calls active/passive causating reason – and finally, as containing or having in something else a reason for actuality – active or passive causality. Like many other Wolffians before him, Darjes goes into great lengths in describing various causal notions, such as principal cause and instrumental cause or mediate and immediate cause, and we need not follow him in such a detail.

Just like almost all Wolffians thus far, Darjes defines the notion of space through the spatial relations an entity could have. Indeed, spatial relations are based on certain connections between entities, in which one entity cannot take the place of the other entities. Such space is then no true entity, but merely an abstraction out of real entities and their relationships. While spatial relationships are completely external to the entities or substances, if one adds activities to the equation, the connection becomes at least more internal. Darjes speaks of presence, by which he means the factor of one substance affecting another – the more a substance affects another, the more present it is to that other substance. Darjesian presence is then a much stronger relationship than mere spatial closeness – if one unites entities by bringing them close to one another, the union is merely external, while a union involving substances being present to one another is internal.

Before moving to more particular parts of metaphysics, Darjes finally considers the notions of infinity and finity, which he defines simply through the notion of perfection – finite entity is such that something can be more perfect than it, while an infinite entity is as perfect as is possible. The finity of an entity does not mean it couldn't be also perfect in some measure. It just isn't completely perfect and all perfection it has must belong also to the infinite entity. It is then immediately clear that all passivity, incompleteness and possibility of non-existence are signs of finity.

Already at this place in metaphysics, Darjes introduces Wolffian aposteriori and apriori proofs of God's existence, although he is, of course, not yet speaking of God. He notes, firstly, that since all finite entities are contingent, they must ultimately depend on a necessary infinite entity. Hence, if finite entities exist, an infinite entity surely must exist also (aposteriori proof). Since it is clearly possible that a finite entity would exist, an infinite entity must also be a possibility. Because infinite entity can be only impossible or necessary, it must then exist necessarily (apriori proof). We see here a similar dual role played by the two proofs as in Wolff's theology, the difference being that Darjes has to assume only the possibility of something finite.

Infinite and finite form then the major division of entities. Infinite entity is essentially unique, so no further division of that species is possible. Finite entities, on the other hand, can divide into further subspecies, depending on whether they are simple or complex.

tiistai 23. tammikuuta 2018

Joachim Darjes: Elements of metaphysics 1 - Forceful being

We have been studying what Darjes calls primary philosophy, but we finally come to his ontology, when we see his definition of an entity (ens). In effect, by an entity Darjes means something that is not accident, that is, which can be in itself. What this being in itself means, according to Darjes, is at least that in the same place as one entity exists, no other entity can exist. Thus, impenetrability of an entity is an ontological characteristic for Darjes, while accidents might share the same place by occurring in same entity. An entity need not exist, but it can be a merely possible entity. If it does exist, Darjes calls it a substance.

Darjes notes that all substances can contain something which is a reason for something else being what it is. In other words, they are forces that can act on other things. Now, because this activity is an essential part of what substances are, they can also be divided according to their level of activity. The highest kind of substance is completely active and needs at most something to remove obstacles from its way to start acting – they are what Darjes calls an effective conatus. At the lowest rang of substances are completely passive substances, which require some efficient reason to make them act – these are what Darjes calls bare potentia. Between these two extremes fall cases where substances are in some sense passive and in some sense active – these substances Darjes calls either ineffective conatuses or potentias with conatus (it is difficult to say whether Darjes means these two to be separate groups, depending on whether the emphasis is on the active or the passive side of the substance or whether they are just two names for the same thing).

Darjes does not just distinguish between different kinds of forces or substances, but also between different kinds of actions these substances can make occur. The actions might happen within the substances or be intrinsic to it – these would be immanent actions. Then again, the actions might also be extrinsic to the substance – these would be transitive actions. Of course, Darjes also admits that some actions might be partially immanent and partially transitive.

Like all Wolffians, Darjes is a nominalist who insists that no universals can exist. Hence, all substances must be individuals. Although substances cannot then be divided into universals and individuals, Darjes does divide them into complete and incomplete substances, depending on whether a substance acts or not. He also notes that a substance can be variably or contingently complete, if it sometimes happens to act and sometimes not. Even if a substance would be contingently complete, it still might be a necessary existent, since there is no necessity that a necessary existent would always act.

A notion near to completeness is the subsistence of a substance. Darjes defines subsistent substance as a complete substance that is not sustained by something else. Here, sustaining means a relation in which one force determines another to act in a precise manner. Thus, subsisting substance would act and not be acted upon by other substances.

Darjes goes on to define states of an entity. In effect, these are nothing more than collections of some determinations that the entity has. For instance, being a substance or substantiality and subsistence are states that some entity might have. Depending on the determinations making up the state, the state can be internal, external or mixed, and it can be necessary or contingent. For instance, if there are some entities existing absolutely necessarily, then they have an absolutely necessary state of substantiality. With contingent entities, on the other hand, their state of substantiality is also contingent and in fact depends ultimately on some absolutely necessary substance.

Darjes does not remain on mere level of definitions, but tries to determine some general characteristics true of all substances, based mostly on the principle of sufficient reason. The most important conclusion is that all substances must persevere in their state of action or non-action, until some further reason makes them change their state. Thus, an action continues, until something comes to impede it.

Darjes also spends some time considering how to quantify forces. His idea is to measure forces through the actions they can make happen. For instance, if two passive substances have the same quantity of force is they are as quick in producing same actions, then they will produce same action in same time. Thus, by checking what the substances can achieve and how quickly they do it, one can compare the quantity of their forces with one another.

Darjes notes that all substances can contain something which is a reason for something else being what it is. In other words, they are forces that can act on other things. Now, because this activity is an essential part of what substances are, they can also be divided according to their level of activity. The highest kind of substance is completely active and needs at most something to remove obstacles from its way to start acting – they are what Darjes calls an effective conatus. At the lowest rang of substances are completely passive substances, which require some efficient reason to make them act – these are what Darjes calls bare potentia. Between these two extremes fall cases where substances are in some sense passive and in some sense active – these substances Darjes calls either ineffective conatuses or potentias with conatus (it is difficult to say whether Darjes means these two to be separate groups, depending on whether the emphasis is on the active or the passive side of the substance or whether they are just two names for the same thing).

Darjes does not just distinguish between different kinds of forces or substances, but also between different kinds of actions these substances can make occur. The actions might happen within the substances or be intrinsic to it – these would be immanent actions. Then again, the actions might also be extrinsic to the substance – these would be transitive actions. Of course, Darjes also admits that some actions might be partially immanent and partially transitive.

Like all Wolffians, Darjes is a nominalist who insists that no universals can exist. Hence, all substances must be individuals. Although substances cannot then be divided into universals and individuals, Darjes does divide them into complete and incomplete substances, depending on whether a substance acts or not. He also notes that a substance can be variably or contingently complete, if it sometimes happens to act and sometimes not. Even if a substance would be contingently complete, it still might be a necessary existent, since there is no necessity that a necessary existent would always act.

A notion near to completeness is the subsistence of a substance. Darjes defines subsistent substance as a complete substance that is not sustained by something else. Here, sustaining means a relation in which one force determines another to act in a precise manner. Thus, subsisting substance would act and not be acted upon by other substances.

Darjes goes on to define states of an entity. In effect, these are nothing more than collections of some determinations that the entity has. For instance, being a substance or substantiality and subsistence are states that some entity might have. Depending on the determinations making up the state, the state can be internal, external or mixed, and it can be necessary or contingent. For instance, if there are some entities existing absolutely necessarily, then they have an absolutely necessary state of substantiality. With contingent entities, on the other hand, their state of substantiality is also contingent and in fact depends ultimately on some absolutely necessary substance.

Darjes does not remain on mere level of definitions, but tries to determine some general characteristics true of all substances, based mostly on the principle of sufficient reason. The most important conclusion is that all substances must persevere in their state of action or non-action, until some further reason makes them change their state. Thus, an action continues, until something comes to impede it.

Darjes also spends some time considering how to quantify forces. His idea is to measure forces through the actions they can make happen. For instance, if two passive substances have the same quantity of force is they are as quick in producing same actions, then they will produce same action in same time. Thus, by checking what the substances can achieve and how quickly they do it, one can compare the quantity of their forces with one another.

perjantai 11. joulukuuta 2015

Baumgarten: Metaphysics – Kinds of substances

The primary

classification of things in metaphysical treatises has long been that

of substances and accidences and Baumgarten's Metaphysics makes no

exception. Substances are things that can exist without being

attached to something else, while accidences have to exist in

something else, namely, in substances. Furthermore, Baumgarten adds,

accidences are not just something externally connected to a

substance, but a substance must contain some reason why such

accidences exist within it. In other words, substance is a force that

in a sense causes its accidences – if completely, they are its

essentials and attributes, if partially, they are its modes.

Now, substances with

modes are variable or they have states, which can change into other

states.

Like all

things in Baumgarten's system, these changes also require grounding

in some forces. Changes effected by forces are then activities of

substances having these forces. Such activities might be connected

with changes in the active substance itself, but they might also link

to changes in other things: these other things then have a passion.

In latter case, the forces might act alone to produce a certain

effect and then we speak of real actions and passions, or then the

passive substance also has some activity at the same time as it has

passions, and then we speak of ideal actions and passions. The

division of real and ideal actions and passions is of importance in

relation to Baumgarten's thoughts about causality.

Because all

substances have forces, all of them have also activities – if

nothing else, then at least activities towards themselves.

Furthermore, activity does not define just the essence of substances,

but also their mutual presence – substances are present to one

another, Baumgarten says, when they happen to interact with one

another.

Baumgarten divides

substances, in quite a Wolffian manner, into complex and simple

substances (Baumgarten does admit that we can also have complexes of

accidences, but these are of secondary importance in comparison with

complexes of substances). Not so Wolffian is Baumgarten's endorsement

of Leibnizian term ”monad” as the name of the ultimate simple

substances. Rounding up the division of substances is the division of

simple substances into finite and infinite substances, in which

infinite substance has all the positive properties in highest grade

and thus exists necessarily and immutably – this is something we

will return to in Baumgarten's theology – while finite substances

change their states and have restrictions.

This concludes

Baumgarten's account of the substances or primary entities of the

world, and like with Wolff, we can already discern the outlines of

the three concrete metaphysical disciples. But before moving away

from ontology, we still have to discuss Baumgarten's account of basic

relations of entities.

torstai 1. toukokuuta 2014

Simplicity itself

As familiar as was his account of

complex entities, as familiar is also Wolff's description of simple

entities, which in many cases simply have characteristics opposite to

characteristics of complex substances. Previously I characterised

Wolffian simple things as units of forces, which is quite correct

still in light of Latin ontology, but one must not assume that

complex entities could not then be described in terms of forces.

Instead, the notion of force is something common to both simple and

complex entities.

To understand what Wolff means by a

force, one must begin with the notion of modes that we know to be

characteristics that can be changed without changing the essential

identity of a thing. Now, consistent collections of modes define a

certain state. Such states, if they happen to be instantiated, belong

to some thing, which can then be called the subject of these states,

which are then adjunct to the subject. Note that the notion of

subject, just like the notion of essence, is context dependent: in

geometry we might take certain figure as stable, while in physics

this figure could also be mutable.

In some cases, the change of states can

be explained through the subject of change – then the change can be

called an action of the subject, while in the opposite case it could

be called passion. Thus, while if I voluntarily jump from a plane,

the subsequent fall is my action, if on the other hand I am thrown

from a plane, the fall is my passion. A subject undergoing an action

can be called an agent, while a subject undergoing a passion can be

called patient.

Furthermore, corresponding to action

and passion, a thing has corresponding possibilities for action and

passion or active potentiality and passive potentiality, the former

of which Wolff also calls faculty. Without these potentialities

actions and passions could not occur, but as mere possibilities they

still require something in order to be activated.

In case of actions, this activating

element is finally called force. What a force is or how it will be

generated should not yet be apparent from this nominal definition.

Still, it is quite clear from the definition that it makes no sense

to speak of a force if there is no action that it activates, unless

there is some opposing force resisting this activation.

This is as far as conceptual analysis

takes us. From empirical considerations Wolff concludes that we could

describe force as consisting of conatus.

Conatus is a peculiar

notion, common to many early modern thinkers, such as Spinoza,

meaning a sort of life force of a thing that aimed at preventing the

destruction of the thing. In physical contexts, conatus

was often identified with impetus, the habit of bodies to remain in

the same state of movement – this tendency was thought to be due to

some internal yearning of bodies.

One obvious aim of

this talk of conatus or impetus is to introduce the possibility to

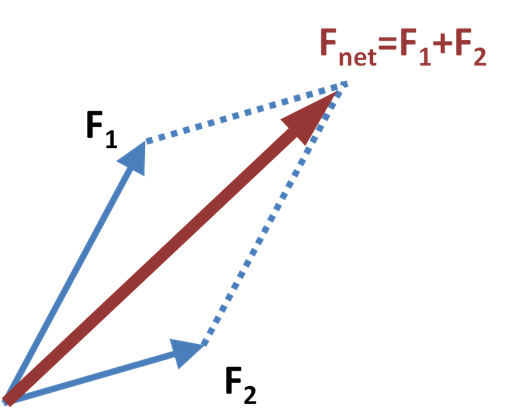

quantify forces – forces can be connected to the actions they

trigger, and we can thus present forces as vectors. Because of their

quantitative nature, forces can be combined (basic principle for this

possibility is easily seen in a so-called parallelogram of force).

Thus, we can regard forces of composite entities as combinations of

forces of simple entities.

|

| Parallelogram of forces: when forces F1 and F2 are the only forces affecting a thing the resulting movement is described by their sum |

The mathematics of

forces is one step in Wolff's project of quantifying philosophy. A

final step is taken with the notion of grade, which Wolff defines as

a characteristic of qualities that can be used to distinguish

different (spatial or temporal) instances of same quality (thus, two

apples might have a different tinge of green). Now, Wolff notes that

it is possible to create at least a fictitious quantification for the

grades (just think of a temperature scale – if a temperature of air

rises two grades, this does not happen because of adding two

individual grades of warmth to air). Because qualities were

originally the only impediment of the quantification program, Wolff

thinks he has solved the problem suggested by his critics.

The final piece in

separating complex and simple entities is the notion of substance.

Here Wolff begins by distinguishing between what is mutable (that

which can be changed without it losing its essential identity) and what is only perdurable (that which can exist for a time without losing its

essential identity). Now, Wolff's interest lies in perdurable things:

cows, shadows, colours, you name it. Some of these perdurable entities are not

mutable, some of them are. According to Wolff, this distinction

among perdurables captures the traditional distinction between

accidences and substances. This might need some explanation. Consider

a traditional example of an accidence, such as certain shade of

colour. It can definitely exist for a while, say, on some surface,

but when you try to change it, it will change into a different shade.

Then again, a substance, like a cow, will not be destroyed, if you

paint it black – thus, it is not just perdurable, but also mutable.

Wolff's definition

clearly is not meant as a strict division, but more as a hierarchy of

substantiality – that is, we can speak of what is more accidental

or substantial. Thus, we can change e.g. shape of a certain blob of

colour, so that it will still remain a blob of this colour. Then

again certain modifications of cow, such as tearing it apart, will

undoubtedly destroy it. In addition, Wolff suggests we may define as

proper substances those perdurables that will endure through any

humanly conceivable change – these are essentially the simple

substances. Then again, complex substances are in comparison

accidental, because all their essential characteristics, such as

figure and magnitude, are mere accidents. Thus, they can be only

secondary substances.

Wolff ends his

account of simple substances with a consideration of infinities. The

characterisation of an infinite substance contains no surprises –

infinite substance is incomparable with finite substances, but we can

say that it has some analogical or eminent characteristics (eminence

appears to be just a roundabout way to say that we really do not understand

what it is). Then again, Wolff also makes some interesting remarks on

mathematical infinities and infinitesimals. To put short, he admits

that no mathematical infinities or infinitesimals actually exist, but

also suggests that such fictions are useful in e.g. differential

calculus.

So much for simple

substances, now it is only relations we have to speak of.

Tilaa:

Blogitekstit (Atom)