Concepts of simple and complex substances were of great interest to Wolffians, being one of the primary divisions of substances, and Crusius seems eager to show where Wolffians wen’t wrong with them. He firstly notes that just like the concepts of part and whole, on which the two former concepts are based on, can actually mean very different things. Starting with the parts, these can mean, Crusius says, any group of things we can represent as forming also a one thing, which then is the respective whole. Furthermore, these parts can be actual or such that they can be separated elsewhere than in our thoughts, but they can also be mere thought parts, which can be distinguished in our thinking, but not really separated.

Simple is then for Crusius something that has no parts - in some sense, while complex is something that has parts - again, in some sense. Since the notion of parts was already twofold, this same duality continues with the notions of simple and complex: something may be simple or complex just based on mere thoughts, but also based on something outside our thought.

Even in case of actual simplicity, Crusius notes, there are various levels of simplicity. The epitome of simplicity, he thinks, is God, who is not just a simple substance - that is, something, which cannot be separated into further substances - but also has a simple essence in the sense that no property could be removed from his essence. This is not always the case, Crusius says, because substance can be simple, like a human soul, without having a simple essence. Even a complex substance, like air, Crusius notes, is simpler than, say, a human body, because the former has only integral parts - parts that all have the same essence - but no physical parts - parts that have a different essence from one another.

Crusius also notes that it is a different thing, if something is simple as such or has nothing separable in it, than if something is simple on the condition that the current world exists, Crusius notes that we cannot really distinguish between the two cases and neither can any finite being, but God might be able to do it.

Every force is in some subject, Crusius insists, because no subjectless forces could be thought of. On this basis Crusius argues that in case of complex substances, their force must be determined by forces of their parts. Crusius then concludes that if a complex substance wouldn’t ultimately consist of simple substances, the constituent forces would have no immediate subject where to subsist, which he thinks is absurd. Despite the seeming complexity of the argument, it appears to just assume what it sets out to prove: that the existence of a complex thing must be based on the existence of simple things.

Crusius is especially keen to distance his notion of a simple substance from a mathematical understanding of simplicity. Mathematics, he says, considers only abstract magnitudes, not other determinations of things. In other words, he rephrases, mathematics is only about the concept of space and its possible divisions. Thus, it was natural for mathematicians to assume the existence of points, which should have even no parts that could be thought of as being outside one another. Yet, Crusius states, no true simple substance is simple in the mathematical sense, but is spatial - they just cannot be physically divided further.

Crusius goes thus straight against the Wolffian notion of elements, which are more like non-spatial forces. If we would accept such non-spatial substances, how could we account for spatial matter being generated from them, especially as any concrete matter would require an infinite amount of them? Furthermore, he continues, we couldn’t even say how such pointlike substances could touch one another, as there are always further points between any two points.

Näytetään tekstit, joissa on tunniste simple things. Näytä kaikki tekstit

Näytetään tekstit, joissa on tunniste simple things. Näytä kaikki tekstit

tiistai 12. heinäkuuta 2022

perjantai 11. joulukuuta 2015

Baumgarten: Metaphysics – Kinds of substances

The primary

classification of things in metaphysical treatises has long been that

of substances and accidences and Baumgarten's Metaphysics makes no

exception. Substances are things that can exist without being

attached to something else, while accidences have to exist in

something else, namely, in substances. Furthermore, Baumgarten adds,

accidences are not just something externally connected to a

substance, but a substance must contain some reason why such

accidences exist within it. In other words, substance is a force that

in a sense causes its accidences – if completely, they are its

essentials and attributes, if partially, they are its modes.

Now, substances with

modes are variable or they have states, which can change into other

states.

Like all

things in Baumgarten's system, these changes also require grounding

in some forces. Changes effected by forces are then activities of

substances having these forces. Such activities might be connected

with changes in the active substance itself, but they might also link

to changes in other things: these other things then have a passion.

In latter case, the forces might act alone to produce a certain

effect and then we speak of real actions and passions, or then the

passive substance also has some activity at the same time as it has

passions, and then we speak of ideal actions and passions. The

division of real and ideal actions and passions is of importance in

relation to Baumgarten's thoughts about causality.

Because all

substances have forces, all of them have also activities – if

nothing else, then at least activities towards themselves.

Furthermore, activity does not define just the essence of substances,

but also their mutual presence – substances are present to one

another, Baumgarten says, when they happen to interact with one

another.

Baumgarten divides

substances, in quite a Wolffian manner, into complex and simple

substances (Baumgarten does admit that we can also have complexes of

accidences, but these are of secondary importance in comparison with

complexes of substances). Not so Wolffian is Baumgarten's endorsement

of Leibnizian term ”monad” as the name of the ultimate simple

substances. Rounding up the division of substances is the division of

simple substances into finite and infinite substances, in which

infinite substance has all the positive properties in highest grade

and thus exists necessarily and immutably – this is something we

will return to in Baumgarten's theology – while finite substances

change their states and have restrictions.

This concludes

Baumgarten's account of the substances or primary entities of the

world, and like with Wolff, we can already discern the outlines of

the three concrete metaphysical disciples. But before moving away

from ontology, we still have to discuss Baumgarten's account of basic

relations of entities.

torstai 21. elokuuta 2014

Matter and forces

An important feature

of world, according to Wolff, is that it is a composite, that is, it

consists of parts. Some of these parts are familiar to us from

experience. Wolff points out that none of these experienced parts are

indivisible, but consist of further parts – we might call them in a

modern philosophical vocabulary middle-sized objects.

As composites, Wolff

continues, everyday worldly objects must be such that can be

completely explained through the structure and mutual relations of

these parts – in effect, they are machines similar to the world

itself. Because of the dependence, one need just change parts of a

middle-sized object in order to change the object itself. In fact,

this is the only way to truly have some effect on these objects.

All the changes on

the bodies require then moving some stuff from them or moving some

stuff in them – that is, movement or motion and direct physical

contact is an essential element in changes of the worldly objects. It

is then no wonder that a huge part of Wolff's cosmology is dedicated

to determining the so-called laws of motion – mostly descriptions of

what happens when several bodies collide with one another, depending

on their size, mass, velocity and cohesion. Although determining what

the correct laws of motion were was an ongoing philosophical and

scientific theme at least from the time of Descartes' Principia

philosophiae, I won't go

into any further details here, besides one exception.

The

one interesting element in the laws of motion is the notion that a

resting body will not by itself start to move and that a moving body

will not by itself change its velocity or direction. This property,

known nowadays as inertia, is called by Wolff a passive force of a

body, and according to him, should be taken as defining what is

called matter, which he takes

to be the extension of passive force.

With just matter, bodies would then just have stayed

in the same place for all eternity. The movement must have then been

generated by something else, that is, by an active force, which is

then transferred from one body to another in various collisions.

Matter

and active forces are then what one requires for explaining the

constitution of our world and

they might be taken as substances in what we observe of the world.

Yet, matter and

active forces are not the whole story. As I've mentioned in a previous text,

beyond the level of material bodies exists the level of elements of

bodies, because as composite entities material bodies must

ultimately consist of some simple entities. As simple, these elements

cannot have any extension and are therefore indivisible. They are not

like atoms are thought to be, Wolff says, because atoms are supposed

to have no true distinguishing qualities, which would contradict the

ontological principle that no two entities can have exactly same

qualities.

The differentiating

principle of the elements, Wolff suggests, should be their conatus,

that is, the basic force containing in nuce all the changes that will

happen to a particular element. In effect, elements are

differentiated by their whole life history. Because an essential part

of a life history of an element consists of its interactions with

other elements and these interactions are essential part of a nexus

forming a world, an element cannot exist except in a single world,

that is, by changing world you must change also its elements and vice

versa.

The actual relation

of elements to bodies is rather confusing in Wolffian philosophy.

What is clear is that elements constitute the realm of bodies we

observe. This means that many features we appear to observe in bodies

must be deceptive. For instance, bodies appear to consist of

continuous masses of such types of stuff as water. Yet, because all

matter and even water must consist of individual, indivisible and

completely distinct elements, they must actually be discontinuous.

What is unclear is how this phenomenal realm of continuities is

supposed to arise from true realm of discontinuities. The question is

muddled even more by corpuscles, which Wolff introduces as

constituting a level between observed bodies and elements. The

behaviour of bodies Wolff explains as constituted by the corpuscles,

parts of body, which still are divisible. Yet, no explanation is

given how corpuscles are generated from the level of elements, and

number of confusing questions remain. For instance, should a

corpuscle consist of an infinity of elements?

This enigma is a

point where we must leave the Wolffian concept of microcosm. Next

time I still have something to say about the order and perfection of

the world in Wolff's cosmology.

torstai 1. toukokuuta 2014

Simplicity itself

As familiar as was his account of

complex entities, as familiar is also Wolff's description of simple

entities, which in many cases simply have characteristics opposite to

characteristics of complex substances. Previously I characterised

Wolffian simple things as units of forces, which is quite correct

still in light of Latin ontology, but one must not assume that

complex entities could not then be described in terms of forces.

Instead, the notion of force is something common to both simple and

complex entities.

To understand what Wolff means by a

force, one must begin with the notion of modes that we know to be

characteristics that can be changed without changing the essential

identity of a thing. Now, consistent collections of modes define a

certain state. Such states, if they happen to be instantiated, belong

to some thing, which can then be called the subject of these states,

which are then adjunct to the subject. Note that the notion of

subject, just like the notion of essence, is context dependent: in

geometry we might take certain figure as stable, while in physics

this figure could also be mutable.

In some cases, the change of states can

be explained through the subject of change – then the change can be

called an action of the subject, while in the opposite case it could

be called passion. Thus, while if I voluntarily jump from a plane,

the subsequent fall is my action, if on the other hand I am thrown

from a plane, the fall is my passion. A subject undergoing an action

can be called an agent, while a subject undergoing a passion can be

called patient.

Furthermore, corresponding to action

and passion, a thing has corresponding possibilities for action and

passion or active potentiality and passive potentiality, the former

of which Wolff also calls faculty. Without these potentialities

actions and passions could not occur, but as mere possibilities they

still require something in order to be activated.

In case of actions, this activating

element is finally called force. What a force is or how it will be

generated should not yet be apparent from this nominal definition.

Still, it is quite clear from the definition that it makes no sense

to speak of a force if there is no action that it activates, unless

there is some opposing force resisting this activation.

This is as far as conceptual analysis

takes us. From empirical considerations Wolff concludes that we could

describe force as consisting of conatus.

Conatus is a peculiar

notion, common to many early modern thinkers, such as Spinoza,

meaning a sort of life force of a thing that aimed at preventing the

destruction of the thing. In physical contexts, conatus

was often identified with impetus, the habit of bodies to remain in

the same state of movement – this tendency was thought to be due to

some internal yearning of bodies.

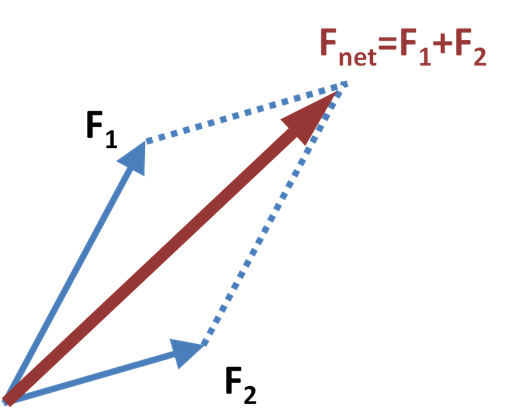

One obvious aim of

this talk of conatus or impetus is to introduce the possibility to

quantify forces – forces can be connected to the actions they

trigger, and we can thus present forces as vectors. Because of their

quantitative nature, forces can be combined (basic principle for this

possibility is easily seen in a so-called parallelogram of force).

Thus, we can regard forces of composite entities as combinations of

forces of simple entities.

|

| Parallelogram of forces: when forces F1 and F2 are the only forces affecting a thing the resulting movement is described by their sum |

The mathematics of

forces is one step in Wolff's project of quantifying philosophy. A

final step is taken with the notion of grade, which Wolff defines as

a characteristic of qualities that can be used to distinguish

different (spatial or temporal) instances of same quality (thus, two

apples might have a different tinge of green). Now, Wolff notes that

it is possible to create at least a fictitious quantification for the

grades (just think of a temperature scale – if a temperature of air

rises two grades, this does not happen because of adding two

individual grades of warmth to air). Because qualities were

originally the only impediment of the quantification program, Wolff

thinks he has solved the problem suggested by his critics.

The final piece in

separating complex and simple entities is the notion of substance.

Here Wolff begins by distinguishing between what is mutable (that

which can be changed without it losing its essential identity) and what is only perdurable (that which can exist for a time without losing its

essential identity). Now, Wolff's interest lies in perdurable things:

cows, shadows, colours, you name it. Some of these perdurable entities are not

mutable, some of them are. According to Wolff, this distinction

among perdurables captures the traditional distinction between

accidences and substances. This might need some explanation. Consider

a traditional example of an accidence, such as certain shade of

colour. It can definitely exist for a while, say, on some surface,

but when you try to change it, it will change into a different shade.

Then again, a substance, like a cow, will not be destroyed, if you

paint it black – thus, it is not just perdurable, but also mutable.

Wolff's definition

clearly is not meant as a strict division, but more as a hierarchy of

substantiality – that is, we can speak of what is more accidental

or substantial. Thus, we can change e.g. shape of a certain blob of

colour, so that it will still remain a blob of this colour. Then

again certain modifications of cow, such as tearing it apart, will

undoubtedly destroy it. In addition, Wolff suggests we may define as

proper substances those perdurables that will endure through any

humanly conceivable change – these are essentially the simple

substances. Then again, complex substances are in comparison

accidental, because all their essential characteristics, such as

figure and magnitude, are mere accidents. Thus, they can be only

secondary substances.

Wolff ends his

account of simple substances with a consideration of infinities. The

characterisation of an infinite substance contains no surprises –

infinite substance is incomparable with finite substances, but we can

say that it has some analogical or eminent characteristics (eminence

appears to be just a roundabout way to say that we really do not understand

what it is). Then again, Wolff also makes some interesting remarks on

mathematical infinities and infinitesimals. To put short, he admits

that no mathematical infinities or infinitesimals actually exist, but

also suggests that such fictions are useful in e.g. differential

calculus.

So much for simple

substances, now it is only relations we have to speak of.

keskiviikko 26. joulukuuta 2012

Johann Joachim Lange: Humble and detailed research of the false and corruptive philosophy in Wolffian metaphysical system on God, the world, and the men; and particularly of the so-called pre-established harmony of interaction between soul and body: as also in the morals based on such system: together with a historical preface on that what happened with its author in Halle: among treatises of many important matters, and with short check on remarks concerning duplicated doubts on Wolffian philosophy - Immaterial materialism

Wolff's deterministic view of the world

is essentially a materialistic doctrine, Lange thinks: immaterial

souls are free to act how they want and their existence should thus

make the world indeterministic. Now, Wolff does admit the existence

of souls without renouncing his determinism, and we shall see next

time how Lange reacts to this strategy.

In addition to souls, Lange sees

immaterialism playing a role already in Wolff's doctrine of world,

particularly in latter's notion of simple substances, which Lange

interprets as essentially identical with monads of Leibniz. This is

yet another point where Wolff himself is truly ambiguous. On the one

hand, Wolff does note the resemblance of his simple substances with

Leibnizian monads and does say that the simple substances in a sense

represent the world. On the other hand, Wolff prefers to speak of

elements and explains that representing is here symbolizing the interconnectedness of all things, because elements are not

literally conscious of anything.

Despite Wolff's skepticism of full

monadology, his doctrine of elements does satisfy some of Lange's

criteria for immaterialism or idealism. Material things, Lange says,

should be spatial and thus should be e.g. infinitely divisible, while

Wolffian elements are not spatial and definitely indivisible. Wolffian matter is thus based on immaterial things and is therefore a species of idealism, which Lange thinks is just as bad as materialism - Wolffian philosophy is then doubly bad, because it combines both idealism (in its doctrine of simple substances) and materialism (in its doctrine of deterministic world).

Lange

is clearly advocating the Aristotelian idea of matter as a

undifferentiated mass, which can be carved out into different shapes,

but which does not consist of independently existing units. While

Wolff does accept his own idea of matter without any proper

justification, Lange is equally stubborn and just states the

self-evidence of his views – matter just cannot consists of

something that is not matter. Lange would probably have been

horrified of the modern nuclear physics, which he would have had to

condemn as even more immaterial – matter consists there mostly of

void together with some small points without any determinate place.

Interestingly, Lange's criticism has

thus far dealt with questions that were later made famous by Kantian

antinomies. Lange believes that world had a specific beginning in

time and thinks that Wolff supposed it to be eternal; he holds

determinism to be broken by free actions of humans and God, while he

assumes Wolff to deny true freedom; and he believes matter to be

infinitely divisible, while Wolff supposed it to consist of

indivisible substances. Strikingly, Lange's anachronistic answer to

second antinomy was diametrically opposite to others, probably

because the doctrine of indivisible substances was associated with notorious atomism.

So much for Lange's views on Wolffian

cosmology, next time we'll see what he thinks of Wolffian psychology.

perjantai 27. tammikuuta 2012

Christian Wolff: Reasonable thoughts on God, world, and human soul, furthermore, of all things in general - Can soul be material?

While in the chapter on empirical

psychology Wolff merely observed the mental capacities of human

beings, in the chapter on rational psychology he tries to determine

the nature of the soul or the thing that has such capacities.

Nowadays it is easy to think such an attempt as completely

ridiculous: after all, Kant should have shown that rational

psychology was based on mere sophistic reasoning. We shall have to

speak of the Kantian criticism in the future. At this point we may

just note the surprising fact that Wolffian theory of the soul begins

with a reasoning of transcendental nature. That is, Wolff begins from

the fact that human beings are conscious of themselves and

investigates the presuppositions of this fact.

The beginning of Wolff's reasoning is

innocent enough. We are conscious of something, Wolff says, when we

can distinguish it from other things. For instance, I am conscious of

a hand mirror, only if I am able to differentiate the mirror from

e.g. hands holding it. Particularly, consciousness of oneself implies

the capacity to distinguish between oneself and other things. In

other words, consciousness is connected with a clarity of thoughts,

which for Wolff meant a capacity to distinguish the object of thought

from other objects.

Furthermore, in order to distinguish

different objects from one another and to recognise them as

different, one must be able to contrast them with one another and to

consider them one after another, Wolff continues. In order to do

this, the conscious being must have imagination and memory, that is,

he must be able to think of things that are not present and to

recognise them as having been present. Indeed, consciousness is

generated, because we can think of a thought for a period of time,

note that the time has changed, but the thought itself has remained.

The arguments thus far have been

essentially about characterising what it means to be a conscious

personality: e.g. a person needs to have a memory, in order that she

would have a sense of continuity of self. I cannot see why Kant or

his followers would have any reason to argue with these

considerations. In fact, much of the Kantian and post-Kantian German

philosophy consists of such theorising on the nature of human

consciousness, although in a somewhat deeper level.

What Kant and his followers would

probably find unacceptable is the next move where Wolff tries to

prove the immateriality of soul or the thing that is conscious. Wolff

starts by noting that all material processes must be explicable

through mere mechanical movement of material objects. Thus, if soul

would be material, thinking would also be such a mechanical process.

Now, human beings can be conscious of their own thinking, that is,

they can note that the starting and the end point of thinking are

different and still parts of a continuous process of one thing. Here

Wolff simply states that such representation of continuity is

impossible with mere matter: material objects as complexes can at

best represent only other complexes, but they cannot represent a

unified process of thought.

Wolff's blunt statement that matter as

a mechanism cannot represent thought processes is quite

unsatisfactory, especially as we nowadays don't think that matter

consists merely of lego-like blocks that interact only through

mechanical contact. Wolff does try to amend his reasoning by noting

that material object can represent things – for instance, we can make a clay model of a building – but it cannot represent the

original as separate from the representation. I have a feeling that

Wolff has here confused first- and third-person perspectives. Surely

an external observer cannot see e.g. brain as a representation of the

process of thought,but this does not mean that the brain could not

represent this to itself, if it just were conscious.

The situation appears even worse, when

we consider that by denying the complexity of the soul Wolff has to

accept the possibility of a simple thing representing complexities,

which appears at least as difficult as a complex representing a

unity. Indeed, how could a single partless entity represent a complex

of many entities correctly? The only possibility appears to be that

the complex is characterised through passage of time: at one point

soul represents one part of the complex, at another point other parts

and at final point the combination of the two previous phases.

Indeed, we might well believe that human consciousness does work in

this manner: e.g. when looking at a boat moving at the sea, we

concentrate first on its rear end and then on the other end and only

after that note that both parts go together.

The problem with this solution is that

it once again threatens the supposed unity of consciousness. Suppose

that I am thinking of myself. This act of thinking then represents

some state of my mind, say, a memory of yesterday. But this act as

simple can only represent one thing, thus, it cannot represent

itself. We could then begin a new act of thinking that had the

original act as its object. This procedure could be iterated

indefinitely and so a problem is revealed: no matter how far we'd go,

there would always be left at least one act of thought that had not

been combined with other acts, that is, the very act of thinking

all the other thoughts. This problematic was something that intrigued

some of the later German philosophers, although Wolff appears to not have noticed it.

Wolff's argument for the immateriality

of the soul was then unconvincing. Next time we shall see whether he

can at least characterise this supposed immaterial entity.

perjantai 18. marraskuuta 2011

Christian Wolff: Reasonable thoughts on God, world, and human soul, furthermore, of all things in general - Lego block view of the world

System builders do love to divide

things into two classes (unless they are German idealists and

probably more into threefold divisions). Wolff follows this tradition

and distinguishes between simple and complex things. (By the way, one

just has to appreciate German language for its capacity to make such

important concepts easy to grasp. Simple things are ”einfache”,

which could be translated as ”one-folded” - simple thing has but

one part. Complex things, on the other hand, are ”zusammengesetzt”

or ”put together” out of smaller things. English equivalents are

less transparent.)

How does Wolff then justify his

division? The existence of the complex or assembled objects he

accepts as given in our experience: the things outside us can be seen

to consist of smaller things. In addition to being assembled of other

things, complex things have various other characteristic properties:

- complex things have a magnitude (after all, they consist of many things)

- complex things fill space and are shaped in some manner

- complex things can be enlarged or diminished and the order of their parts can be varied without changing anything essential

- complex things can be generated by putting things together, and they can be destroyed by separating the constituents

- the existence of the complex things is always contingent

- the generation of complex things takes time and is humanly intelligible

Simple things, on the other hand,

cannot be found in the experience, Wolff says, so their existence

must be deduced. Here Wolff invokes the principle of the sufficient

reason: the existence of a complex thing cannot be explained

completely, unless there is some final level of things from which the

complex thing has been assembled. These simple things have then

characteristics completely different from the complex things:

- simple things do not have any magnitude

- simple things do not fill space nor do they have any figure

- simple things cannot change their internal constitution (because they do not have one)

- simple things cannot be assembled from other things nor can they be disassembled; they can only be generated ”at a single blow” (einmahl)

- simple things are either necessary or generated through something necessary

- the generation of simple things is atemporal and non-intelligible to humans

Wolff's scheme reminds one probably of

atomism, yet, atoms have usually not been described as non-spatial: in this Wolff's simple things resemble Leibnizian

monads. Yet, if we ignore for now the nature of space, which I shall

be discussing next time, we can discern a common pattern shared by

atomism, Leibnizian monadology and Wolffian ontology of simple and

complex things.

This pattern is based on the idea that

world is like a game with legos. There are magnificient buildings and

vehicles, but they are all made out of small objects – lego blocks

– which in themselves cannot be broken down to smaller pieces. No

complex of legos is necessary and you can even see the revealing

lines that tell how to disassemble a ten-story castle into individual

blocks. Indeed, in all the various combinations, lego blocks remain

distinct individuals that just happen to be attached together.

The lego block view of the world is so

common these days that it is difficult to remember other

possibilities. It was different with Aristotle, who in his physical

studies casually notes that substances might also be mixed, that is,

combined in such a manner that the combined substance vanish and a

new substance appears in their place. We may easily picture such a

mix through an example of adding sugar to water: the powdery sugar

vanishes, but also mere water, and in place of the two a sugary

liquid appears.

One might oppose my example with the

observation that the sugar and the water do not really vanish when

mixed, but sugar molecules merely disperse among the water molecules.

Yet, this observation itself is based on empirical studies and one

could not decide a priori whether

this particular case was a true mix or a mere assembling of lego

blocks. In other words, the example shows that Aristotelian mixes are

a conceivable possibility. Furthermore, it is also a possibility

which we could well comprehend and imagine: we could model any Aristotelian

mix through the picture of sugar combining with water.

Indeed, we need

even not think of mixing two substances of different sorts. It

suffices to picture a portion of water combining with another portion

of water. The result is not two portions of water, but one bigger

portion, or in other words, the original things have vanished in

combination and been replaced by a new thing. This conceptual

possibility is ingrained in the mass terms of some languages: things

like water do not appear to behave like the lego block model, thus,

we cannot e.g. speak meaningfully of several waters (we have to speak

of many portions of water etc.)

If the possibility

of an Aristotelian mix is admitted, Wolff's whole division of simple

and complex things becomes somewhat suspect. The simple things

should, on the one hand, be the ultimate constituents, which are

required for explaining the existence of the complex objects: they

should be the independent substances, while the complex substances

are contingently assembled from them.

Then again, simple

things should, on the other hand, be indivisible and they could not

have been generated through a combination of other things. Yet, if a

thing has been or at least could have been generated through an

Aristotelian mix, it would not be simple in the second sense, while

it well might be simple in the first sense, that is, an independent

substance. In other words, a substance might be generated from other

substances, but still not have any parts or constituents.

Wolff himself

actually considers the possibility that a simple thing could just

change into other simple things, somewhat like Aristotelian elements

– fire, air, water and earth – can change into one another. Yet,

he quickly disregards this possibility, because either it would be a

miracle where one substance is instantly destroyed and another takes

it place or then the apparently independent things are mere states of

one thing. Only with the latter option, Wolff adds, does the previous

state explain the latter state.

Wolff's denial of

Aristotelian change of elements is itself unfounded. Even less

convincing it is as a criticism of an Aristotelian mix. Although an

apparent change of one thing to another thing should be interpreted

as a mere change of state, an Aristotelian mix involves a combination

of several things into one unified thing, and it feels rather awkward

to call two separate things a mere state of their combination or vice

versa.

The flaw in Wolff's

division of things is important, because it suggests a similar

flaw in Kant's second antinomy. The antinomy should consist of two

equally convincing statements that could not hold at the same time:

”everything in the world consists of simple things” and ”there

is nothing simple in the world”. The two statements could well be

both true, if the simple things in the first statement meant final

constituents of assembled things, but the simple things in the second

statement meant indivisible substances. That is, the final

constituents might have no parts, but they could be so manipulated that

in place of a particular thing, many things would appear (this division is

essentially a reverse of the Aristotelian mix, and indeed, Aristotle

himself apparently thought divisions worked this way). We shall have

to return to the issue when we get to Kant's Critiques (it will

probably take twelve years).

Wolff's theory of

simple and complex things has other problems as well. For instance,

Wolff merely assumes that simple things cannot be observed. He does

not mean that we could not imagine what simple substances would be

like, and indeed, he admits that we perceive very small things as

having no discernible parts. Yet, Wolff notes that magnifying glasses

have proven that these apparently simple things are actually complex

– but this empirical evidence does still not prove the general

inobservability of simple things.

A more substantial

reason for the unobservability of simple things is Wolff's conviction

that simple things cannot be spatial, while all observable things

are. But why simple things couldn't be spatial? This is a question I

will consider next time, when I investigate Wolff's theories of space

and time.

Tilaa:

Blogitekstit (Atom)